Nolan Killman ’26: The Resnek Family Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

- The Rivers School

- Oct 20, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

Since I was little, every time I'd hear some incredible fact about the human body, or about the intricacies of the ways diseases progress within our cells, I always wondered, “How on Earth did anyone ever figure that out?” I couldn’t comprehend how each complex detail in the science books I would read needed, at one point, to have been discovered for the first time. For eight weeks this summer, I was lucky enough to have been able to participate in the generation of that very knowledge. As an intern at the Resnek Family Center for Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, led by Dr. Josh Korzenik, I’ve been able to work on a variety of studies aimed at navigating the pathophysiology and best courses for treatment of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and related diseases.

PSC is a rare, autoimmune liver disease that attacks the bile ducts and causes severe damage to both the liver and gallbladder. The disease’s cause, along with the process through which it attacks the bile ducts, is relatively unknown, and there is no known treatment for the disease other than a complete liver transplant, which most PSC patients will ultimately require. At the Resnek Center, Dr. Korzenik and his team investigate PSC through many clinical and translational research studies, which are carried out in collaboration with sites around the world. More specifically, much of Korzenik’s research focuses on the strong correlation between PSC and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), which is a chronic disease that inflames the colon and affects over 2 million Americans. IBD comes in two forms: Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and Crohn’s Disease, the former being more likely to coincide with PSC (around 70% of PSC patients are also diagnosed with UC).

Coming into this internship, I assumed that medical research only involved long hours in labs, or at computers compiling data. What I didn’t expect was to witness a live colonoscopy within minutes of arriving at the office – a true testament to the connection between research and clinical medicine. I quickly learned how Dr. Korzenik, a practicing gastroenterologist, is able to integrate the experience and knowledge he gains from his clinical practice into the research being done at Resnek.

Later that first day, I began work on some of the translational research studies being done by the Center. One of my first tasks was to extract data from records of patient visits for a prospective study on the progression of adults with IBD. This study aims to discover more effective ways to determine which drugs to prescribe at certain points in the progression of the disease. I began to learn about the different markers of IBD progression and the methods in which they were treated, including common medications and procedures. I would record any changes in the patients’ symptoms, medications, surgical histories, or lab results across every visit since the patient was consented.

Additionally, I was asked to sort through patient records to determine whether certain samples were eligible for a new study attempting to determine biomarkers (certain indicators to check disease progression) for PSC, UC, Crohn’s, and a myriad of other related conditions. As I became more involved in that study, I was tasked with extracting data from hundreds of patient records about medications, disease activity, lab work, and more in order to have a full background on each sample being processed in the study, which allows for a more complex analysis and impactful results.

While I spent a lot of time on the data analysis side of research, I was also able to dive into some hands-on lab work. Before we sent samples off to be tested for biomarkers in the same study mentioned above, we needed to divide, or “microaliquot” each sample tube into 16 smaller quantities in order to run many different assays on the same plasma sample, thus testing it for a wider range of possible biomarkers. I was often able to participate in the microaliquoting process, where we would use a machine to automatically pipette predetermined amounts of sample into the smaller tubes. I worked to prepare samples for microaliquoting by thawing, centrifuging, and sometimes manually pipetting the plasma into a different tube. I learned immediately the precision and practice required to complete procedures in the lab, for when dealing with blood samples, your goal is to have them out of the freezer for as little time as possible in order to preserve sample quality. I knew to study the Standard Operating Procedure and take notes when observing the first few aliquoting runs so I could carry them out with the required efficiency.

When carrying out research studies with hundreds and sometimes thousands of samples like the larger studies at Resnek, a large amount of time spent on that study goes into keeping meticulous records of each of the samples’ locations. With each of the studies I was a part of, I was able to help with the logistical aspect of medical research and log precisely when a sample was moved, processed, or created. Often, this required visits to the Brigham and Women’s “Freezer Farm,” where a multitude of research labs store their samples and equipment. I once again learned to be precise and quick when handling study samples, and was able to participate in mass freezer transfers involving transporting the samples on dry ice and precise record keeping so the team would be able to find the sample later. On the other side of this logistical process, I also created sample manifests using our storage records to facilitate the processing and microaliquoting needed for certain studies.

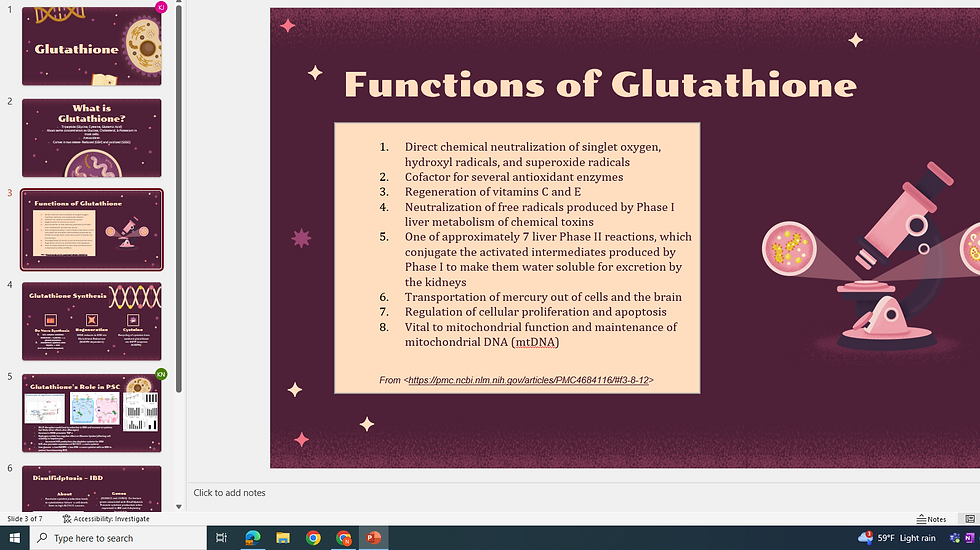

For my last week at Resnek, Dr. Korzenik asked me to put together a brief presentation for the team on Glutathione: an antioxidant that plays a pivotal role in Resnek’s hypothesis for the cause of PSC. My presentation was one of many that the team presented to each other each Friday at our weekly Lab Meeting (which always featured a lunch order from a place of the team’s choosing). Through the presentation of these personal projects, we were able to gain a better understanding of PSC and IBD as we worked toward the conclusion of the larger studies. These presentations, along with the manner in which studies were conducted at many collaborating institutions at once, taught me the importance of collaboration in medical research, and how each discovery made is the result of the work of an army of researchers. Further, through my brief talk on Glutathione, I got a taste of the process behind starting a research project from scratch, and the importance of coming up with questions to drive your research.

During my time at Resnek, I cemented my love for the field of medicine and learned the incredible ways in which medical research is inseparably tied to practical medicine, as exemplified perfectly by Dr. Korzenik himself. I also gained an immense appreciation for the amount of logistics, complexities, and effort that goes into any single step of a research study. Even over my short time at Resnek, I was able to witness the completion of certain smaller studies and see the immediate impact that the results can have on our understanding of these rare diseases, and thus the reality of those who live with them. This experience has shown, among much else, the integral role that medical research plays in our daily life, and the real impact that these discoveries can, and will continue to, have on people afflicted with all kinds of conditions. I couldn’t be more grateful to Mr. Schlenker, Dr. Korzenik, and the rest of the Resnek team for this incredible opportunity.

Comments